One of the most interesting phenomena in recent times in Cuba is, undoubtedly, the high level of empowerment that the people are demonstrating. The so-called average Cuban, so often maligned both on and off the island, has become the perpetual protagonist of demonstrations of all kinds and sizes in a process that the regime finds alarming and that overturns the most common stereotypes about what power is and how it is accumulated and deployed. Despite all the real and concrete evidence in recent times, it is still very often heard (too often, perhaps) that Cubans just want to leave the country, that if they are given a little food they will calm down or, as I have heard some "Cubanologists" claim, they lack the ability to seek change for themselves.

Nothing could be further from reality. It is curious that these arguments come, in most cases, from people who are outside the country and, therefore, enjoy peace of mind because they eat whatever they want every day and do not need or seek changes in their daily routines. These are unfair arguments advanced by people totally disconnected from the Cuban reality. The truth is that the criticisms that might be leveled in relation to Cubans' inability to organize and pose an important civic challenge to the system are so slight that they pale before the facts and figures pointing in just the opposite direction.

It should be noted that this is not something coincidental or fleeting. When a phenomenon is recurs in time and space it ceases to be speculation and becomes a trend. The events of 11-J are an example of this type in Cuba; thousands of Cubans took to the streets across the country demanding freedom, democracy, and an end to the dictatorship. The protests lasted until July 12 and 13 and, according to calculations by various NGOs and independent observers, both inside and outside Cuba, the number of participants exceeded 100,000 in more than 50 towns and cities all across the country, in what was, to date, the most significant non-violent action on the island.

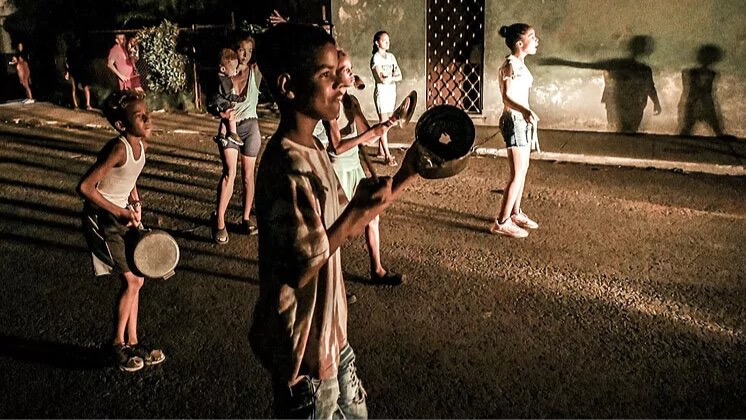

That impressive display of power in numbers, beyond the subsequent repression, also led to concessions by the regime, which, although initially minimal, such as repairing certain streets or restoring homes in specific places, were succeeded by relaxed Customs regulations and other measures in the economic sphere, demonstrating a process of action and reaction that must be encouraged and reinforced. The equation is presented as follows: if people protest, the regime gives in somehow; it is all a question of how they protest and what their demands are. After 2021 there have been hundreds of miniature 11-Js every year, like the aftershocks of that massive earthquake, which shook up patterns of behavior that defined citizens' relationship with the State.

This is nothing new, but rather accords with precedents set across time and space. Successful movements in history have managed to escalate their demands from minimalist campaigns to maximalist ones. Surprisingly, some people believe that demonstrations are counterproductive and that it is advisable for change to come from the top down, soft landings mislabelled "transitions", another abused term. Historical experience teaches us that dictatorial regimes, especially those of a Communist nature, do not change or begin to engage in dialogue out of some sudden epiphany. As the etymology of the word suggests, there must be a transit, a shift from one system of government to another, from one set of political and social relationships to another, and for this another transformation is essential: one in the people's mentality.

An excellent study by Freedom House, entitled “How Freedom Was Won: From Civil Resistance to Enduring Democracy,” demonstrates with facts and figures how Eastern European countries that saw people-driven changes, in a non-violent way, forged democracies (Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, etc.), while those that underwent top-down changes (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, etc.) ended up with new forms of dictatorship.

What is happening in Cuba is a redefinition of power relationships as a result of actions that generate results — as slight as they may seem at first— being taken by Cubans confronting situations of oppression. Yesterday it was in Caimanera, the day before in Santiago de Cuba. Tomorrow who knows where it will be, but what is certain is that this unrest will recur, and this undermines the system's capacity to respond, as it cannot put out fires at the same time it is forced to employ selective repression in a vain attempt to induce fear. The protests continue, when and how the people want them to; maybe not at the rate some would like to see, but at the pace at which the people are marching.

At the end of the day, the people are setting the pace, not an old dictator in danger of extinction, or foreign visions of any kind. Whoever controls the clock manages the dynamics of any conflict. Thus, it is no use crying over spilled milk because, in Cuba, the situation has reached a point where people pick it up again however they can, to ease their hunger. Faced with such a harrowing situation, academic disquisitions or café philosophies lose whatever relevance they might have in other contexts.

When will all these processes come together to produce a final result? No one has a crystal ball to predict this. But, in the meantime, it is more prudent to encourage action rather than scorn it in favor of some supposedly supreme intellectual reason. Rather than being relevant, it is necessary to be effective. After all, as the great Cuban poet José Ángel Buesa would say, hurrying has never been elegant.